Despite punishment for speaking their own language in government boarding schools and not having voting rights in their own states, approximately 400 Americans became their nation’s secret weapon during World War II – the Navajo Code Talkers.

Today, most people in the United States have heard about code talkers in passing conversations, but few have looked into the history of the code talkers.

“It’s important to know this piece of history because it had such a profound impact on World War II and it’s something we can all be proud of,” said Chief Warrant Officer 4 John Hawthorne III, who has researched the Navajo Code Talkers’ training at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, Calif. “[American Indians] are just one of those pieces that make up the American mosaic. It’s not just their history – it’s my history – it’s American history.”

The Navajo Code Talkers were part of a classified program that began with Philip Johnston. The son of a Presbyterian missionary to the Navajos, he was one of the few outsiders at the time who spoke the unwritten Navajo language. Johnston, a veteran, was familiar with the military’s small-scale use of American Indian languages during World War I.

In early 1942, Johnston met with Maj. James E. Jones, the force communications officer at Camp Elliot – modern MCAS Miramar, and proposed using the Navajo language as a military code because it was difficult to learn without exposure at a young age and incomprehensible to non-Navajo speakers.

On Feb. 28, 1942, four Navajos demonstrated their capabilities to encode, transmit and decode a message in 20 seconds during a field test at Camp Elliot. Maj. Gen. Clayton B. Vogel, the commanding general of Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet, was impressed by the demonstration and asked the commandant of the Marine Corps to approve the program.

“The demonstration was interesting and successful,” wrote Vogel in his letter to the commandant March 6, 1942. “Mr. Johnston stated that the Navaho* is the only tribe in the United States that has not been infested with German students during the past twenty years. These Germans, studying the various tribal dialects under the guise of art students, anthropologists, etc., have undoubtedly attained a good working knowledge of all tribal dialects except Navaho. For this reason the Navaho is the only tribe available offering complete security for the type of work under consideration … It should also be noted the Navaho tribal dialect is completely unintelligible to all other tribes and all other people, with the possible exception of as many as 28 Americans who have made a study of the dialect. This dialect is thus equivalent to a secret code to the enemy, and admirably suited for rapid, secure communication.”

The Marine Corps recruited 29 Navajo men during the next two months and on May 4, 1942, the recruits left Fort Defiance, Ariz., for basic training in San Diego. All 29 Navajos, who made up their own platoon, graduated basic training.

Following their graduation, the Marines marched directly to Fleet Marine Force Training Center at Camp Elliot where they received courses on transmitting messages and radio operations.

During their time at Camp Elliot, the 29 Navajo Marines constructed the code, which consisted of an alphabet and accurate replacement phrases for military terms. The alphabet used words to represent letters, such as “wol-la-chee,” or ant, for the letter A, and “dzeh,” or elk, for the letter E. For military terms, they used replacements such as “da-ha-tih-hi,” or humming bird, for a fighter plane, and “gini,” or chicken hawk, for dive bomber. The Navajos’ creation contained 211 replacement terms and phrases. Any military phrases that didn’t have replacements were spelled out.

The Navajo Code Talkers had their first field test in July 1942. The Coast Guard mistakenly picked up on a transmission and reported it as strange and possibly hostile.

After completing their training, the original 29 code talkers were assigned to several divisions bound for the South Pacific. A few remained at the school, which was later moved to Camp Pendleton, Calif., to train incoming Navajo Marines.

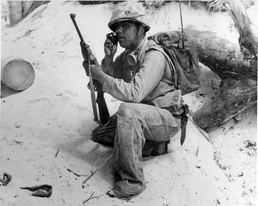

After reporting to their units, the code talkers saw action on several South Pacific islands including Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Saipan, Guam, Palau and Okinawa. One of the most important and bloodiest battles of the South Pacific, Iwo Jima, was one of the code talkers’ finest examples of proficiency. During the battle, six Navajo Code Talkers sent more than 800 messages without error.

“Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima,” said Maj. Howard Connor, the 5th Marine Division signal officer for whom the six Navajo Code Talkers worked during the first 48 hours of battle.

While serving overseas, the Navajos had to constantly update their code to prevent repetitiveness and frequently used words from being discovered by the Japanese. Commonly used letters, such as E, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, L and U, had several alternative words. Overall, the code grew to more than 400 phrases and words for the code talkers to memorize.

“My weapon was my language,” said the late former Navajo Code Talker Joe Morris Sr. in a San Bernardino park on Veterans Day in 2004. “We saved a lot of lives.”

Following WWII’s end, the code talkers were ordered to keep the code a secret in case America needed to use the code again – which it did on a small scale in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts.

The code talkers remained silent about their time as Marines until 1968 when the code was declassified. Recognition came later when former President Ronald Reagan signed a proclamation of the first National Navajo Code Talkers Day on Aug. 14, 1982.

“The Navaho Nation, when called upon to serve the United States, contributed a precious commodity never before used in this way. In the midst of the fighting in the Pacific during World War II, a gallant group of men from the Navaho Nation utilized their language in coded form to help speed the Allied victory,” said Reagan in his proclamation. “Equipped with the only foolproof, unbreakable code in the history of warfare, the code talkers confused the enemy with an earful of sounds never before heard by code experts. The dedication and unswerving devotion to duty shown by the men of the Navaho Nation in serving as radio code talkers in the Marine Corps during World War II should serve as a fine example for all Americans.”

On July 26, 2001, four of the five living 29 code talkers received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award, from former President George W. Bush. The other 25 code talkers’ families received the medals in their places. Navajos who became code talkers later in the war received the Congressional Silver Medal. The medals featured two Navajo Code Talkers speaking on a radio to reflect their achievement.

“It is indeed an honor to be here today before you representing my fellow distinguished Navajo Code Talkers,” said the late John Brown Jr. during the Congressional Gold Medal presentation at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. “We must never forget that these such events are made possible only by the ultimate sacrifice of thousands of American men and women who, I am certain, are watching us now … [Of] the original 29 code talkers, there are just five of us that live today: Chester Nez, Lloyd Oliver, Allen Dale June, Joe Palmer and myself. We have seen much in our lives. We have experienced war and peace. We know the value of freedom and democracy that this great nation embodies. But our experience has also shown us how fragile these things can be and how we must stay ever vigilant to protect them, as code talkers, as Marines. We did our part to protect these values.”

Today, only 90-year-old Chester Nez remains of the original code talkers. Overall, it is estimated that less than 70 code talkers are still alive.

The Navajo Code Talkers honorably served their country during a time when they did not even have the right to participate in Arizona or New Mexico state elections. They stood for honor, courage, commitment and the American dream that all men have the right to live free.

*Navaho is a common spelling for the tribe in historic documents