On Dec. 31, 1776, Col. John Cadwalader, a senior leader in the Pennsylvania militia, provided detailed intelligence on the British position and forces in Princeton, New Jersey. This gave General George Washington the critical information he needed for his next attack on the British on Jan. 3, 1777.

After his victory at Trenton on Dec. 26, 1776, General Washington looked for another opportunity to strike the British. He continued to press his subordinates for intelligence on the enemy forces and their intentions. On the last days of 1776, Col. Joseph Reed, Washington’s adjutant general, led a patrol of the Philadelphia Light Horse toward Princeton. They explored the roads and took some prisoners. Interrogation of the prisoners revealed that Lord Charles Cornwallis had reinforced the town with 8,000 troops and now intended to move against the Americans at Trenton. Reed also noted the British were not using the back roads in the area.

Meanwhile, 14 miles to the south, Colonel Cadwalader was also gathering intelligence on the British forces in the vicinity of Princeton. A merchant from Philadelphia, the 34-year-old Cadwalader had been elected the commander of the Philadelphia Associators, a brigade-sized volunteer militia group. Unable to get over the Delaware in time for the battle of Trenton, he and his Associators crossed the river into New Jersey on Dec. 27. Based in Crosswicks, about 20 miles to the south of Princeton, Cadwalader and his 1,800 men began patrolling the area and harassing the British whenever possible.

On Dec. 30, Cadwalader sent “a very intelligent young gentleman” to gather information on the enemy in Princeton. The young man—who remains anonymous to history—returned the next morning with detailed information on the British force and its disposition. He reported about 5,000 British and Hessian troops in the area. These troops were fatigued and, more importantly, were not guarding the east side of town.

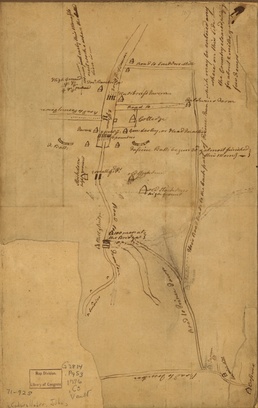

With his report of the “gentleman’s” information, Cadwalader included his own “rough draft” of the road from Crosswicks to Princeton. The map was detailed and included useful annotations. Along the main eastern road, Cadwalader noted, “This road leads to the back part of Princeton which may be entered anywhere on this side—the country cleared, chiefly, for about 2 miles... few fences.” The map even noted the high ground in the area. Not only did it include the road network, but it also gave the strength of the guards at the bridges and the locations and number of cannons. Moreover, it showed existing defensive works and postulated future ones, noting when they would be completed.

Based largely on the reports of Reed and Cadwalader, General Washington made his plans for an attack against the British. He sent a blocking force to delay Cornwallis’s troops moving toward Trenton. Then, on Jan. 3, he moved his main force along the unguarded back roads and attacked the British in Princeton. The result was another success. In short, intelligence was a key factor in the first American victory of 1777.

Article by Michael E. Bigelow, INSCOM Command Historian. New issues of This Week in MI History are published each week. To report story errors, ask questions, request previous articles, or be added to our distribution list, please contact: TR-ICoE-Command-Historian@army.mil.