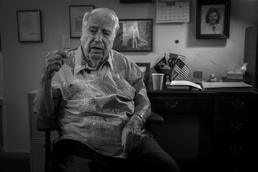

Prescott Valley, Arizona, is a warm and sunny far cry from the brutal camps where the Japanese held American prisoners of war on mainland Japan during World War II. Peter B. Marshall has known both places intimately.

Marshall is the last living survivor of the American prisoners of war taken from Guam to mainland Japan at the start of WWII.

Growing up in the midst of the Great Depression, Marshall’s family had no car, no electricity, no indoor plumbing, and no indoor heating. The nearest school, which his father built, was miles away. From an early age, he remembers walking three miles to school each day.

Everything that Marshall’s family had was either made by them or bought in trade. His father, a farmer, worked very hard to yield his crops and maintain one of the best gardens in town. In addition, his father ran a small-home tomato canning factory, owned a blacksmith shop, a fence-making machine, and a mill for which he could provide other services.

Marshall’s mother raised pedigree chickens, selling their eggs to the hatchery, and sold cream and male calves. When it came to feeding her children, hot cereal with milk, cornmeal mush, and rice were staples. Corn was eaten in season and meat was prepared, if one of the kids caught a squirrel or rabbit, earlier that day.

Despite all of this, he and his siblings always had plenty of food and warm clothing; they lived a good life, Marshall said.

“After high school, there were no jobs,” he explained. “So I joined the Navy when I was 18. I had no trouble with the training in Great Lakes, Illinois, and after training, we were given ten days of boot leave to go home.”

Marshall did not know, however, that this would be the last time he would see home until late 1945.

Marshall’s unique experience in the Navy helped him overcome the many obstacles he’s faced in his life, including outliving many of his beloved friends and family members.

Upon his return from boot leave, Marshall didn’t know what job he wanted, so he chose to become a hospital corpsman. He passed the school with high grades, and received orders to start working in the surgery ward at US Naval Hospital San Diego. There, he quickly became proficient in his specialty.

Marshall never thought that he would be sent overseas, yet he got orders to report to the destroyer base to be transported to Guam. He had never even heard of Guam. He may as well have been given orders to the moon; it was all foreign for him. Marshall left for Guam February 5, 1941.

Marshall was assigned the night shift at the naval hospital in Guam. One night, a patient had a heart attack and Marshall called the officer on duty. While he waited, he prepared the operating room and even had the first syringe, which he knew the incoming doctor would ask for, ready. Seconds later, Dr. Van Peenen, the doctor on duty, urgently rushed in the room and asked for a syringe, which was handed to him by the young, calm Marshall.

After the incident, Van Peenen spoke with Marshall and told him that he was impressed with how Marshall had handled the situation. He asked Marshall to work with him as his instrument nurse in the operating room and Marshall agreed. Marshall quickly became Van Peenen’s favorite instrument nurse, learning which hand to place the instruments in and always providing the doctor with the appropriate tool.

On December 8, 1941, Dr. Van Peenen was late to work; he was never late. In Hawaii, six hours behind Guam by the global time zones, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had begun. The U.S. was officially at war. The consequences for Guam, a tactical location for the enemy, were going to be swift and terrible.

That’s when the hospital commander decided that all of the worst cases were to be sent to Van Peenen’s operating room, and that Marshall and Van Peenen were not allowed to leave the room. Lunch was brought to them by the commander himself; they ate their sandwiches as he solemnly explained that the Japanese were all over the island and that by tomorrow, they would either be killed or captured.

The next day, Marshall and his compatriots were prisoners of war. Marshall and 19 others were selected to care for the remaining patients, all crammed into a single ward. Later, the Japanese called the 20 outside to face a line of machine guns. This was a firing squad, and Marshall was forced to face his imminent execution. Their captors were laughing and joking while they recited Japanese propaganda to the prisoners.

“The smirks on their faces turned my utter fear into utter hatred,” Marshall said.

Marshall quickly made peace with death and vowed that he would die with honor and not do anything to shame his beloved country. The stress of the machine gun ordeal left Marshall, a man with remarkable memory, unable to remember the following three weeks.

At the hospital, there was no time to relax, because the guards were always bothering the prisoners or mistreating them. A month later, when the hospital prisoners were being moved to the town of Zentsuji, Japan, they met up with another group of prisoners that was being held outside the hospital. They told horrible stories to Marshall and the others of beheaded Marines and meager daily rations of one potato a day. At Zentsuji, the men were put to work in the mountains, moving heavy rocks.

Just as the prisoners had gotten used to the schedule of the hard labor in Zentsuji, the prisoners were moved again, this time to Osaka. Marshall realized that he and the others were “in it for the long haul.” The war was not going to be over soon, and he was sure the prisoners were going to be at the camp for a while. All of the prisoners started forming groups of two or three, for the sake of increasing their chance of survival.

Marshall formed a bond with Alfred Mosher and Albert Schwab. The three vowed to look out for each other. They agreed that if any one of them received special items, like soap or food, that it would be split among them. Another condition was that if one of them got sick, the other two would take care of him.

One day, Marshall realized he was having trouble breathing. There was a fluid filling his lung cavity, partially collapsing the lung. Marshall was terrified because getting sick in the camp meant death. He witnessed several prisoners get sent to the medical hospital, but come back a hollow shell or never return at all.

Marshall didn’t want to be put on the sick list, so he did his best to keep it a secret from the guards. Mosher and Schwab helped him every night to the top shelf, his “bunk,” in the small, cramped room where the prisoners slept. He believes that their help is one of the reasons that he is still alive today.

“They kept telling me, ‘Just breathe, dammit!’” he explained. “At the time it was very difficult for me to breathe, I could only breathe sitting up.”

On June 1, 1945, on a work detail, Marshall heard the loud hum of a dozen mechanical beasts overhead: a group of B-29 Superfortresses. The aircraft began to pummel the camp below with bombs that crackled and breathed death with each monstrous roar, hoping to remove the Japanese presence. The American bombers were unaware that this was a prisoner camp, so the attack lasted a long four hours. The camp was so damaged that the Japanese were forced to relocate the prisoners to Fushiki.

Months later, Marshall, on another work detail, saw all the Japanese guards gathering around a radio, listening like their lives depended on it. Within minutes the guards deserted the camp, leaving just the prisoners and one Japanese guard who spoke English. The guard told the prisoners that he would help them as best he could, but getting food would be a big problem.

Japan surrendered shortly after, and Marshall and the others were promptly air-dropped food and cigarettes. They were soon picked up and taken back to Guam for medical examinations September 8, 1945. Marshall had been a prisoner of war for 1,368 days: the entire duration of the war in the Pacific Theater.

When Marshall returned home, he discovered that his father, whom he had not seen for more than four years, had passed away during his captivity. Marshall was heartbroken that he never gave his father a hug, or told him that he loved him.

Marshall had a difficult time adjusting back to normal life during the 90-day rehabilitation that the prisoners received. During his time home, he met Faye Elder through a friend. The two went on several dates, and he knew he wanted her to be his. He proposed right before he left for the U.S. Naval Hospital in Norman, Oklahoma.

There, Marshall was struck with tuberculosis, and had to spend the next two years in numerous hospitals until he was medically discharged from the Navy.

Although he was upset, he figured that now was the perfect time to start tending to his family. Together, the Marshalls had two daughters, Cynthia and Beverly, who enjoyed a close-knit family. The two warmly remember their father, and how he took great care of them.

“My dad has always been my hero,” Cynthia said. “As a little kid, he was always there. Daddy was strong and he was handsome, and he took good care of us.”

Peter Marshall is now the last living prisoner of war who was captured from Guam during World War II. He resides in Prescott Valley, Arizona, with his daughters, whom now take care of him.

Marshall’s wife, Faye, passed away in 2013; she is buried in National Memorial Cemetery in Cave Creek, Arizona, an hour away from Prescott Valley, and where Marshall plans to be buried when his time comes. Together they will be in good company, alongside veterans, heroes, and those who heard their nation’s call.