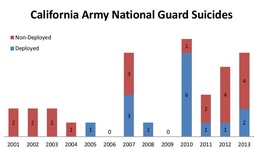

SACRAMENTO, Calif. - In the California Army National Guard, there have been 36 confirmed suicides since 2001, including 28 since 2007. The worst year was 2010 with seven confirmed suicides, followed by three, five and six.

In an effort to prepare leaders to step in and help at-risk troops, and to develop a mentality of resilience among Guard members, experts in the California Army Guard conduct suicide prevention training about once a week up and down the state.

“The Army used to be more reactive but now is becoming more proactive,” said California Army Guard suicide prevention program manager 1st Lt. Herbert Campos.

Campos said Soldiers have a culture that values strength and not admitting weakness. That culture has prevented many from seeking help, he said, and changing that culture is part of what his classes teach.

“Stigma-reduction is huge,” Campos said. “If you can take care of yourself, you can better take care of others. … You’re strong if you ask for help.”

Fifteen of the 36 suicides in the California Army Guard since 2001 were committed by Soldiers who had deployed at some point in their career, including three that occurred during a deployment and two that occurred while the soldier was on transitional leave following a deployment. The other 10 all occurred at least one year after deployment.

Deployments and combat exposure, however, are not a leading cause of suicides, according to Capt. Nathan Lavy, coordinator of the California Army Guard’s Resilience, Risk Reduction and Suicide Prevention Program. National statistics cited by Lavy show that young soldiers with deployment experience have historically been less likely to choose death by suicide than those who have never deployed. He noted that deployments provide camaraderie, friends and shared experiences, which typically decrease suicide risk.

The demographic group at greatest risk, according to the data, is white men aged 17 to 24 years who have experienced behavioral health issues. All but three of the California Army Guard suicides since 2001 were committed by men.

“Young Soldiers who haven’t deployed, have not integrated entirely into the Army and lack coping and life skills, in general, are at higher risk,” Lavy said.

Common factors among troops who consider suicide include relationship issues, financial problems, unemployment, legal issues and familiarity with suicide due to relatives having killed themselves. “Most of the time, it’s a combination of factors,” Lavy said.

Experts in the CNG teach Soldiers the Resilience Trainer Assistants Course; Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training; Ask, Care, Escort-Suicide Intervention; and Master Resilience Trainer Course. Each provides a different level of training to help members in every rank deal with adversity and assist others who may be at risk.

Air Force Lt. Col. Susan Pangelinan, the CNG behavioral health coordinator, said Guard members who experience psychological or emotional distress should visit the CNG webpage, www.calguard.ca.gov, and click the “Behavioral Health” link toward the bottom. That will provide contact information for behavioral health clinicians in every part of the state who can assist Guard members and direct them to resources to help them through tough times.

“For every challenge they are experiencing,” she said, “there is an avenue for help.”

Pangelinan added that a simple examination of suicide statistics does not necessarily indicate the true cause of a trend. For example, the high number of young, white men who have committed suicide could be reflective of that demographic group’s large representation in the Army.

She added that the rise in military suicides in recent years is reflective of an overall trend in society. According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall suicide rate in the U.S. population increased from 13.7 per 100,000 people in 1999 to 17.6 per 100,000 in 2010.

“We mirror the population that we draw our soldiers from,” Pangelinan said. “The social fabric is not as consistent, supportive and all-encompassing as before.”

In the past, companies provided pensions, good health care plans and more benefits for the duration of one’s career, she said.

“What you have is a new generation that never had that level of support,” she said, adding that young people today face challenges ranging from high student loan burdens to a shaky employment picture, and many have not developed the coping skills that come with age and experience.

Pangelinan also noted that the Army Guard and Army Reserve face several challenges that the active duty force does not when it comes to tracking and preventing suicides.

“When you’re on active duty, they own you 24/7,” she said. “In the Guard, because they don’t belong to us 28 days a month, we may not always know that each death was caused by suicide versus accidental with the same fidelity that active forces know. … We don’t have the automatic infrastructure that you have on an active base with all of the support agencies in one location.”

In response to the challenges of tracking and preventing suicides, the Cal Guard established a Community Health Promotion Council last year. The council, comprising 26 representatives from the various directorates in the California Military Department, meets quarterly to improve resilience, overall well-being and readiness within the Cal Guard through education, training and internal and external resources.

“This is another prong in our multi-faceted approach to combating suicide and improving behavioral health,” Pangelinan said. “This is a fight that requires constant re-evaluation to remain effective, and we are committed to doing all we can.