NEW ORLEANS - Born July 15, 1920 and died March 15, 2013, William A. Barnes is now Clarksdale, Miss.’s most legendary resident. As he rests in peace in Jackson, Miss., Barnes shares citizenship with fellow Mississippi Delta luminaries such as Robert Johnson, Tennessee Williams and W.C. Handy. While the bluesman Johnson sold his soul, Williams his plays and Handy, the very art and business of blues, Barnes sold life dearly to enemies of his country but gave it freely to rescue those in peril as a true blue-suiter Coast Guardsman.

Unlike them, however, Barnes is a full-fledged member of the Greatest Generation. This is a club so elite there is no card, just a bullet-holed dog tag and perhaps some scars, memories or pieces of lead still embedded unbeknownst. One could say they regard aches and pain as merely weakness departing the body.

Originally, Barnes waited in line to sign up with the U.S. Navy, but the line was too long. He then enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Following an initial assignment to the Manhattan Beach Coast Guard Training Center in New York and a short stay at the Merchant Marine Academy, he was assigned to the USS PC 590.

Barnes served as a gunner for a 20-mm anti-aircraft machine gun on the bridge of the PC 590, which was a patrol craft and submarine chaser in the Pacific theater during World War II. He is credited with damaging or destroying several Japanese aircraft, including some possibly flown by Kamikaze suicide pilots.

From there, he and his shipmates sailed to Pearl Harbor to begin the task of escorting large convoys of battleships, supply ships, tankers and troop transports to combat zones in the South Pacific. In the nearly two years he spent aboard PC 590, there were no losses among the ships escorted by the cutter. In 1945, a typhoon struck the American fleet supporting operations around Okinawa. The anchor line of PC 590 broke during the storm and the cutter crashed into a reef. The crew was rescued by their comrades on nearby ships despite the dangers of typhoon conditions, but PC 590 broke apart and became partially submerged.

"It was a terrible sight to see them take an ax and cut that towline, Barnes remembered. "We got stuck in a crater and stayed there for five days. We went wherever Mother Nature took us."

Now adrift in the most isolated part of the Pacific, Barnes and the crew drifted for 62 days - right into the cradle of a reef. The hull plating tore, split and collapsed like breaking waves. Fast currents from the typhoon thrust the ship straight toward the Sea of Japan.

"We were almost to the waters of Japan, and, we didn't know a submarine was right below us," Barnes recalled. "They surfaced right next to us all of a sudden. I swung my 20-mm around. Then, I saw the most beautiful thing in the world - raising of the American flag."

During those two months while either adrift or dead in the water, the crew ran out of food. A carpenter's mate cannibalized some wire from one of the ship's service generators and made fishing line.

"We had salmon for breakfast, salmon for lunch, and you guessed it - salmon for dinner," Barnes said.

After 60 days adrift near Midway Island, a troop convoy ship arrived and towed the PC 590 back to a dry dock in Pearl Harbor.The crew disembarked to what was known as a marine rest area, where they stayed at none other than the Royal Hawaii Hotel.

"It was the swankiest hotel in the world," said Barnes. "They served us five meals a day - no salmon of course."

After 10 days of rest and relaxation, Barnes and his shipmates boarded a repaired PC 590 and resumed the mission of escorting battleship convoys. On Aug. 15, 1945, the Empire of Japan surrendered and cemented the end of the war and the total victory of the Allies over the Axis powers. Barnes ended his service Nov. 28, 1945. The remaining four months of his service as a yeoman he helped other Coast Guardsmen process discharges.

Before he passed away, Barnes donated his original World War II petty officer 1st class uniform, vintage photographs and service memorabilia during an official commemoration ceremony at the Mississippi Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby, Miss., Nov. 16, 2013.

Right up to his last days, he gave a part of himself freely. He literally could not wait to serve. For, he went from the shortest line of the Coast Guard recruiting office in 1941 all the way to that long blue line of sterling shipmates who man the rails of the hallowed halls of our nation’s history.

There is no app for honor or heroism on a smart phone, but if one googles William A. Barnes, they will soon discover his life was the steady application of decency and dedication. He and a dwindling number of veterans of World War II are dying at a rate of more than 600 a day.

As a result, there are approximately 1.2 million veterans remaining of the 16 million who served in World War II. There is the 99 percent, the one percent, and there are the two-fifths of one percent of the American population who gave some. And, with their last breath, they gave all. Forget them we will not.

Barnes, like many of his band of brothers, is now a hero of history. As each of them pass, a torrent of 300 million tears rain the hearts of a grateful nation. "I hope that we have set a good record that you can live up to. It really was a worldwide war, because we were all over the world it seemed. I just ask you please be careful as you can and always support this great nation," Barnes concluded during an oral history interview Nov. 28, 2012, in hospice at his home in Jackson.

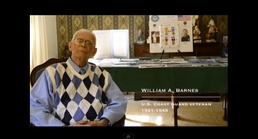

Click on the video to hear Mr. Barnes in his own words. For his family and friends, he shared the following final thoughts:

http://www.dvidshub.net/video/285174/heroes-history-memory-pearl-harbor-veteran-william-barnes